【連載】これから演劇を始める人のための演劇入門 ENTRANCE=EXIT, FOR STARTING THEATER― 第2場「演劇」という看板はあなたの未来か? The doorplate of “theater” is your future?

これから演劇

2018.12.4

*藤原ちからによる新連載。コンセプトについてはこちらをご覧ください。

*English is bellow the picture, you can translate into your language easily.

* * *

わたしは今、バンコクの暖かい「冬」の中にいます。実はこれが初めてのタイ訪問ですが、首都バンコクの発展ぶりには驚きました。バックパッカーを魅了するカオスな町並みや、安くて美味しい料理が今もあるのは事実です。けれども、東南アジアに付きものの「エキゾチック」なイメージだけでは、この都市の実際の規模や活力を認識することは不可能でしょう。この世界は絶え間なく更新され続けており、古いイメージではその実像を捉えることができません。そしてどの都市もそうですが、ここにもやはり複雑な背景があります。若くて、優しくて、たくましい人々の笑顔を見ていると忘れそうになりますが、タイは軍政下に置かれていて、次の選挙がいつ行われるかも不透明なのです。

さて、ここには滞在制作のために来ていますが、最初の数日間はBIPAM (バンコク国際舞台芸術ミーティング)に参加しました。東南アジア各地から来た舞台芸術のプロフェッショナルたちに会い、いくつかのショーとディスカッションに大きな刺激を受けました。もしかするとわたしは批評家としては、マレーシアのファイブ・アーツセンターによる『Gostan Forward』という作品について語らなくてはいけないのかもしれない。ジャーナリストとしては、熱く議論された「持続可能性」についてしっかりとレポートを書いたほうがいいのかもしれない。でもここでは、そういった詳細よりもっと手前の、すごく基本的なことを確認してみたいと思います。なぜこれが「舞台芸術」のミーティングなのかということ。「演劇」の、ではなく。

近年アジアでは、舞台芸術に関する国際的なミーティングや見本市が増えています。もともとTPAM (東京芸術見本市→舞台芸術ミーティングin横浜、1995年〜)、APAM (オーストラリア舞台芸術見本市、2002年〜)、PAMS(ソウル舞台芸術見本市、2005年〜)がありましたが、特に近年、台北のADAM(アジアが見出すアジアのコンテンポラリーパフォーマンスのためのミーティング、2017年〜)、BIPAM (バンコク国際舞台芸術ミーティング 、2017年〜)が誕生。さらには APP (アジアのプロデューサーによるプラットフォーム、2014年〜)もやはり舞台芸術にフォーカスしています。

これらのミーティングは「演劇」だけにフォーカスせず、「ダンス」や「パフォーマンスアート」や「音楽」、そしてそれらにカテゴライズできないパフォーマンスも含んでいます。

もちろん、この世界にはたくさんの「演劇」祭があります。しかしミーティングとなると、「舞台芸術」にフォーカスしているケースが目立ちます。これらのミーティングは基本的にはプロフェッショナル向け、つまりプロデューサーやアーティスト向けのものであり、一般の演劇の観客はこの問題について特別な関心がないかもしれません。とはいえこうしたミーティングの場で蓄積されている議論は膨大にあり、その結果として培われているネットワークと信頼関係はかなり強力なものです。そして商業的・政治的な条件に振り回されがちなフェスティバルと違って、ミーティングではより未来のビジョンについて話し合うこともできます。あなたはこれらのミーティングにおいて、才能や情熱に溢れた人たちに出会えるはずです。この種のミーティングの重要性はこれからさらに増していくでしょう。

その国際ミーティングの場が、「演劇」だけではなく「舞台芸術」にフォーカスしているのはどうしてでしょうか?

* * *

「演劇」と「舞台芸術」の違いについて、アジア各国の状況を見てみましょう。

中国では、わたしの狭い観察範囲によれば、「演劇」は「舞台芸術」よりも保守的に見えます。おそらく最大の理由は検閲でしょう。もしも演劇作品を中国でつくろうとするなら、事前に当局に台本を提出しなくてはなりません。そのため例えば上海では、美術館の教育普及部門の枠を使ったパフォーマンスが盛んに行われています。背景には美術館の建設ラッシュという事情もありますし、この状況がどこまで続くかはわかりませんが、今のところ、それは中国に住むアーティストにとって活動を続けるための一種の抜け道になっています。彼らはそれらを「演劇」とは呼ばないでしょう。けれども、まぎれもなくそれらは「舞台芸術」の一部ではあります。

韓国では、また別の事情があります。ソウル市内にテハンノと呼ばれる演劇の町があり、そこに多くの小劇場がひしめいていることはよく知られています。この点だけを見れば、ソウルは「演劇」の都市であると言えるでしょう。けれども、韓国で10年ほど前に生まれた文脈を見過ごすわけにはいきません。2006年、韓国政府が「ダウォン芸術(多元芸術)」と呼ばれる新しいジャンルをつくり、それをサポートし始めたことによって、「演劇」や「ダンス」や「映画」といった特定のジャンルに属さない何かが「ダウォン芸術」として認知されるようになったのです。その結果、「ダウォン芸術」の影響を受けた若い演劇人も少なくありません。仮に彼らが「劇団」に所属していたとしても。

フィリピンにはまた異なる状況があります。「演劇」は彼の地において教育や啓蒙のために有用ですが、そのスタイルは少しばかり保守的に映るかもしれません。「演劇」から多くを学んだ若い世代のアーティストは、彼ら独自のやり方を、他のジャンルとも接続可能な「パフォーマンス」として始めています。強権的な政治や、治安、貧困、公害といった様々な社会的問題に直面している彼らにとっては、「演劇」の看板を死守することよりも、彼らの可能性を拡張することのほうがはるかに重要なのです。

では、日本はどうでしょう?

* * *

少し前に、わたしは日本である少女に出会いました。彼女は生まれ故郷から出て東京の大学に進学しようとしています。彼女にはすでに舞台経験があり、これからたくさんのことを学べば、将来はもっと素晴らしいパフォーマーになるかもしれません。もし、わたしがいかにも「演劇」人らしく振る舞うならば、彼女に東京で大女優になる夢を見せることも可能だったかもしれません。チェーホフの『かもめ』における、少女ニーナに囁く作家トリゴーリンの権威的・誘惑的な言葉が危険であるように、若者に対する大人の言葉は常に危うさを孕んでいます。それは夢を見せもするし、幻影を見せもする。わたしは自分の言葉の責任について考えました。

この10年ほどの日本での活動において、わたしは「演劇」の概念を拡張する方法によって、「これは演劇ではない!」と否定する声と闘ってきたように思います。それによって「演劇」の自由度を増やそうと試みてきました。ここでは詳しくは語りませんが、ヨーロッパから輸入された「ポストドラマ演劇」の影響や、「コンテンポラリーダンス」との緊張関係によって、日本では「演劇」が延命できたという事情もあったと思います。幸いなことに、様々な人々の努力の結果として、日本の「演劇」は確かにずいぶん自由になりました。けれども、わたしがこの延命戦略に加わったのは正しい選択だったのでしょうか? いっそのこと、「演劇」はブラックボックスの劇場の中で行われるものとして留めて、それはそれできちんと大事にしながら、別の枠組みで新しいチャンスを探る方法もあったのではないでしょうか?

正直、わたしは複雑な気持ちです。なぜなら、この連載もまた「演劇」にフォーカスし、その可能性を拡張しようと試みているからです。この連載の最初にお話したように、「演劇」には独自の歴史があり、あなたはそこから多くを学ぶことができるでしょう。しかし「演劇」という概念がわたしの目には時々、麻薬のようなものとして映るのです。非常に中毒性の高い麻薬として。

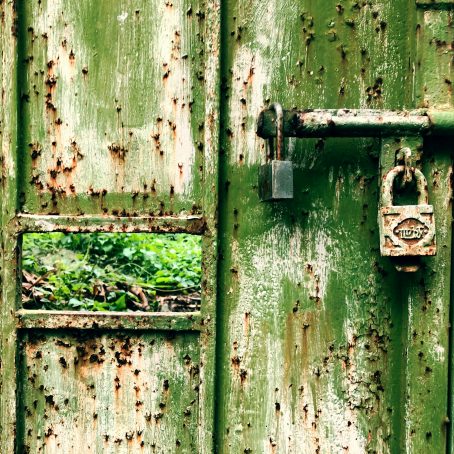

わたしは迷っています。「演劇」の名前を保持したままのほうがいいのか? それとも、「演劇」という看板にこだわることをやめて、「舞台芸術」のような他の概念に頼ったほうがいいのか? ひとまず、これから「演劇」を始める人たちには言いたいと思います。もしもこの概念があなたを縛り付け、思考停止させ、好奇心を奪っているとしたら……あなたはこの麻薬のような概念から離れなければならないと。

……結局、わたしはその少女に「演劇」を勧めることができませんでした。東京の「演劇」が彼女の才能を台無しにしてしまうことのほうを怖れてしまったのです。それはわたしにとってショックなできごとでした。つまりわたしは「演劇」を信頼できなかったということです。わたしはただ、彼女が「演劇」も含めたいろんなスタイルのパフォーマンスに触れてほしいと願いました。彼女には未来があります。「演劇」がその芽を育てるかもしれない。けれども、「演劇」以外の何かがそれを育てるかもしれない。

あなたなら、彼女にどんな言葉を伝えますか?(ハッシュタグ #korekara_Q )

I’m now in the warm “winter” of Bangkok. Actually this is my first visit to Thailand, I was really surprised about the development of this capital city. There are still chaos streets, cheap and delicious foods which attract backpackers. But by only the “exotic” image which are often put to South East Asia, you cannot recognize this actual scale and vitality of this city. This world continues to be updated constantly, old images cannot capture the real figure. And like as every city, there are also complex backgrounds. As looking at smiles of people who are young, gentle, and lively, sometimes I forgot the fact that the Thailand is under the military government. No one knows when they can hold the next election.

By the way, I came here for my artist residency project. During the first few days, I joined BIPAM (Bangkok International Performing Arts Meeting) and met a lot of professional people of performing arts who came from South East Asian countries. Some shows and discussions were very stimulating for me. Perhaps as a critic, I may have to talk about “Gostan Forward” by Five Arts Center of Malaysia. Or, as a journalist, I may have to write a deep report on hotly discussion about “sustainability”. However, here I would like to confirm a very fundamental thing in front of those attractive details. That is, why is this the “performing arts” meeting? Not “theater”?

In Asia, this kind of international meetings or markets for performing arts are increasing. There are already TPAM (Tokyo Performing Arts Market → Performing Arts Meeting in Yokohama, since 1995), APAM (Australian Performing Arts Market, since 2002), and PAMS (Performing Arts Market in Seoul, since 2005), but especially recently, ADAM (Asia Discovers Asia Meeting for Contemporary Performance, since 2017) in Taipei, and BIPAM (Bangkok International Performing Arts Meeting, since 2017) was born. And APP (Asian Producers’ Platform, since 2014) is also focusing to performing arts.

It means, these meetings are not only focusing to “theater”, but also including “dance” and “performance art” or some “music” and performance which cannot be categorized.

Of course, in the world, there are many “theater” festivals. However, in the meetings, in many cases they focus on “performing arts”. These meetings are basically for professionals, including producers and artists, so ordinary theater audiences may not be particularly interested in this matter. However, there are enormous discussions accumulated at these meeting places, and the networks and reliable relationships cultivated here are quite powerful. Unlike festivals which are often influenced by commercial and political conditions, meetings can discuss the future visions more. You should be able to meet some talented and passionate people at these meetings. The importance of this kind of meetings will be increasing more and more.

Why are the international meetings focusing in “performing arts”, not just in “theater”?

* * *

About the difference between “theater” and “performing arts”, let’s see the situation in Asian countries.

In China, in my narrow range of observation, “theater” seems conservative than “performing arts”. Probably the biggest reason is censorship. If you are planning to make a theatrical work in China, you must submit a script to the authority in advance. Therefore, for example in Shanghai, performances using framework of museum’s education department are actively conducted. In this background, there are circumstances about the construction rush of museums, and I don’t know how far this situation will last, but for now this is a kind of a hidden way for artists living in China to continue their activities. They never call them “theater”, but undoubtedly they are part of “performing arts”.

In Korea, there are other circumstances. It’s well known that Seoul has a theater town called Daehangno, many small theaters are crowded in this town. If you look only at this point, Seoul can be said to be a city full of “theater”. However, don’t overlook the context born in Korea around ten years ago. Since 2006, the Korean government created a new genre called “dawon art (multi-disciplinary art)” and began supporting it. This “dawon art” has been recognized as something that does not belong to a specific genre such as “theater” or “dance” or “cinema” etc… As a result, some of young theatrical people in Korea are influenced by this “dawon art” even if they are belonging in “theater company”.

In the Philippines, there are also different situations. “Theater” is useful for education and enlightenment there, but the style may seem already little bit conservative. Young generation artists who learned a lot from “theater” started their own way as “performance” which can connect with other genres. They are now faced to the social issues like forcible politics, security, poverty, pollution etc., so it’s more important for them to expand their possibilities than to defend the doorplate of “theater”.

So, how about Japan?

* * *

A while ago, I met a girl in Japan. She is planning to enter the university in Tokyo, leave her hometown. She has some experience as a performer already, and if she learn a lot from now, may be more wonderful performer in the future. If I behaved as a “theater” person, maybe I was able to show her a dream of becoming a famous actress in Tokyo. A word form adult to young is always dangerous, like the words with temptation and authority to Nina from Trigorin in Chekhov’s “Seagull”. It shows a dream, it also shows a illusion. I thought about the responsibility of my word.

In terms of my 10 years activities in Japan, by the way of expanding the concept of “theater”, I fought against the negative voices like “This is not theater!” or something like that. By this way, I tried to increase the freedom of “theater”. I cannot say the details now here, but, by the influence of “post-drama theater” imported from Europe, and by the tense relationship with “contemporary dance”, “theater” was able to extend its life in Japan. Fortunately, as a result of the efforts of various people, Japanese “theater” has definitely become more free. But, was it correct choice that I joined to this strategy to extend its life? Maybe I should consider and respect “theater” as something in blackbox theaters, and could explore new opportunities with different frameworks?

To be honest, I have a complex feeling, because this article series are also focusing “theater” and trying to expand its possibility. As I mentioned at the beginning of this article series , “theater” has the own history, and you can learn a lot of things from that. But sometimes for my eyes, the concept of “theater” seems drug. Very addictive drug.

I’m wandering. Should I keep the name “theater”? Or, should I not stop sticking to the doorplate of “theater” and rely on other concepts like “performing arts”? Anyway, just I want to say to people who will start “theater” from now. If this concept restrained your body, stopped your thoughts, deprived your curiosity… You should depart from this kind of addictive concept.

…Finally, I couldn’t recommend “theater” for the girl. I was afraid of the danger of “theater” in Tokyo spoiling her talent. It was a terrible shock to me. In other words, I couldn’t believe in “theater”. I just hoped that she will touch various styles of performance including “theater”. The girl has future potentials. “Theater” may grow its buds. However, something other than “theater” may also grow it.

If you are, what kind of words will you tell her? (hashtag #korekara_Q )